The East London Gymnastics Centre (ELGC) is facing closure due to housing development plans, putting the future of elite and community gymnastics at risk.

Since freeholders sold the site to housing development group Galliard Homes, ELGC managers Alex Jerrom and Kirk Zammit fear they will be replaced by tenants who can afford higher rates.

They have launched a petition as they look to secure the future of the gym which has trained some of the top gymnasts in the country, including Paris 2024 athlete Georgia Mae Fenton.

The fate of the ELGC has come under threat after the site it is on was bought by Galliard Homes.

Once a deal was made, ELGC was assured they could negotiate their tenancy with the new owners.

Jerrom said: “They simply replied that the redevelopment was no longer viable, and that was it.

“Later, they called to say they would keep the site for leisure, but we wondered why we hadn’t received an offer to stay.”

In response, Galliard Homes claimed to be committed to retaining the building and ensuring its financial viability.

They said: “We have secured a new tenant who will bring significant health and social benefits to the community.”

Despite Zammit and Jerrom’s concerns about poor communication, Galliard Homes disputes their claims.

Galliard Homes added: “Since agreeing to purchase the site, we have kept existing tenants informed of our plans, including the decision not to move forward with a residential-led development.”

Opened in 1998 with National Lottery Funding, ELGC in Beckton has long been a cornerstone of the gymnastics community.

Jerrom and Zammit have operated the club as a non-profit charity since 2015 and take pride in its contributions to elite gymnastics.

Zammit said: “There is so much history at this club, even before this place was built, we’ve had multiple British champions and GB team members competing at Worlds and Euros.”

Zammit described the club as a hub of London regional gymnastics.

He said: “We currently have two girls on the GB team and another on the Polish national team.

“Next year, we are likely to have three more girls join the GB team, more than anyone else in Greater London.

“Without this facility, future Olympians won’t have anywhere to train.”

Beyond gymnastics, the centre impacts the broader community by supporting various groups and businesses, including a circus school.

Despite the progress of the ELGC, the prospect of closure is becoming increasingly likely.

Jerrom said: “There’s no other facility that’s affordable and large enough for us to move into, so we will be forced to close the club down.”

They worry that in a low-income area like Newham, the changes brought by developers are part of a trend of closures.

Zammit added: “In Newham, there used to be four leisure centres, but two are closed, and one is soon to close.

“Soon, there will be one leisure centre in the entire borough.”

Many similar spaces have already been lost, including The Hub, a vital dance space, Overgravity, a tricking gym in Bow, and Parkour Generations Chainstore, significantly impacting arts and sports communities.

There are also concerns that new tenants will not maintain the community impact of ELGC, with fears that developers will favour economic gains over engagement.

Jerrom said: “They’re likely to bring in something like a fitness gym or a bowling alley.

“Leisure is such a broad category that it won’t be a community centre or hub, and it won’t foster social interactions.

“The friendships and lifelong connections built here are invaluable.”

Beyond elite sports, the gym serves as a sanctuary for community members who benefit from its positive impact on well-being.

Zammit added: “Many people come here for help with their mental health, social anxiety, and self-confidence.”

This motivation drove Zammit to take over the East London Gymnastics Centre.

He reflected: “My life would have been completely different without sport giving me focus.

“I grew up in a rough area of East London, and the old East London club was where I first trained.

“I know what these kids are putting into their sport, and they need support.

“When my Mum couldn’t afford to get me to the gym, people made sure I could continue training because of their passion for the sport, and that’s why this is so important.”

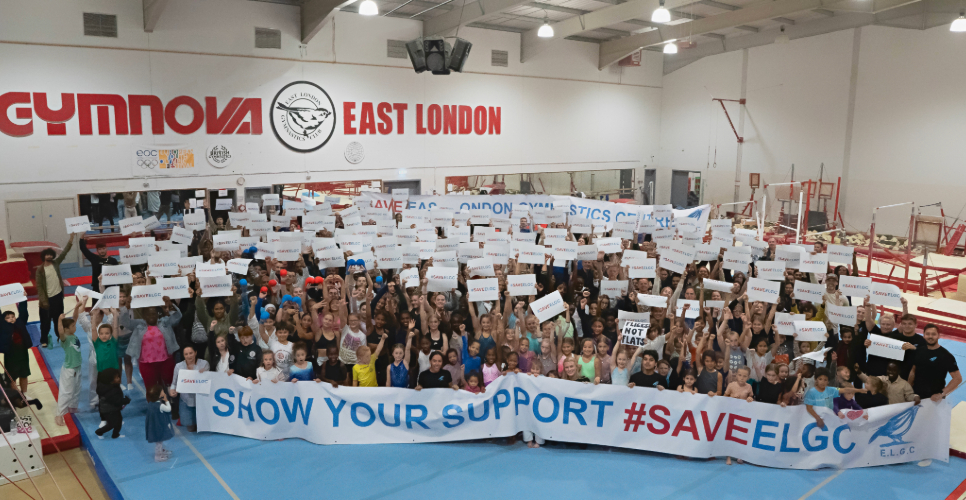

Determined to fight the closure, Zammit and Jerrom have launched the SAVE ELGC Campaign.

James Asser, MP for West Ham & Beckton said: “I am truly saddened to hear of the risk of closure faced by ELGC.

“Having visited the facility I can see that it is an invaluable asset for not only those in the Beckton community, but for everyone who is passionate about elite sport across London and nationally, having trained some of our Team GB athletes.

“Losing such a resource would be a tragedy for the individuals who train at and are supported by the centre, and I will work with all those involved to insure it remains as an invaluable part of my community.”

Featured image provided by ELGC – permission to use