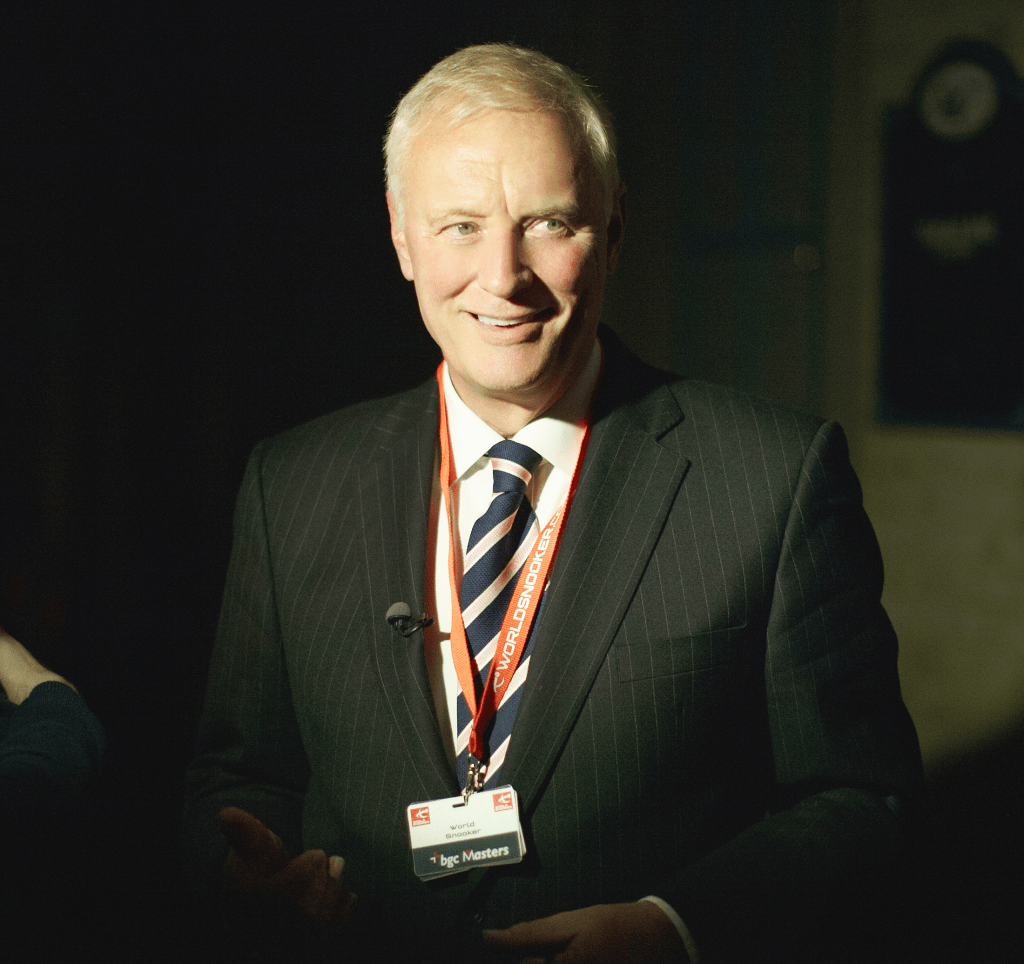

Credit: Image by Matt Fowler, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons. Link.

Raucous fans, fancy dress, packed arenas. A sport once tied to local pubs is now prime time, global entertainment. And behind it all is Barry Hearn, the larger-than-life promoter whose Midas touch elevated darts from smoky boozers to the Ally Pally stage. This is how he did it.

Through his company, Matchroom Sport, Hearn has become one of the most influential figures in darts, eventually serving as chairman of the Professional Darts Corporation (PDC) until 2021. Reflecting on his journey on his podcast ‘The Barry Hearn Show’, Hearn shared how he transformed darts from pub entertainment to a global spectacle.

In the early 1990s, the British Darts Organisation (BDO) was struggling, and in a transitional phase for the sport, the PDC broke away, determined to carve out its own path. They approached Hearn, already a successful promoter of snooker, boxing, and football, hoping he could work his magic on darts.

“You never know when an opportunity is going to slap you in the face, and the good Lord smiles,” Hearn jokes.

He recalls meeting trailblazing figures who were passionate about darts, with a vision of where it should be and frustration that it wasn’t there yet. It was at The Circus Tavern, a local venue in Essex, where Hearn saw the potential of darts and was immediately hooked.

“You couldn’t see across the room for smoke,” Hearn recalls.

“There were bookmakers in the corner, people betting on 180s, who’d hit a 170 checkout, the big fish. They were having a few beers and chanting with their mates.

“But in front of them, through all this atmosphere, was world-class sport. And I thought, if I wanted a night out, I’d come here.”

For Hearn, it was more than a business opportunity; darts was a passion project. He was drawn to the people, the stories, and the atmosphere surrounding the sport.

“I could see in darts, even back then, I liked the customers,” he adds.

“They were ordinary people from where I came from, just wanting a good night out. Nothing complicated.”

That sentiment holds true today, with the fan culture and atmosphere preserved as darts has ascended to the big leagues.For darts to have its current reputation, Hearn also credits the players and their personalities, whose charisma contributes to the sport’s excitement.

He hilariously recalls the late Jocky Wilson, a darts legend, dampening fellow pro Rod Harrington’s party piece of catching a dart mid-flight by stabbing him in the belly with another dart.

“Jocky was on the floor in hysterics, and Rod was just looking at his shirt as a trickle of blood rolled down. No lasting damage, but that was darts,” Hearn laughs.

Darts, however, isn’t about practical jokes. Behind it are players who want to win, but these individuals, who honed their skills in pubs and clubs, knew they had to entertain.

“In working men’s clubs, you had to be interesting, or people wouldn’t come to watch,” Hearn says.

“You needed a quick line, a shout-back, an answer.”

Perhaps none did this better than the ‘Crafty Cockney’ Eric Bristow. Around Bristow, Hearn built the characters that now captivate darts fans.

“He had persona. He had charisma, and he didn’t give a monkeys. Fans would throw beer cans at him, and he thought it was hilarious, knowing he’d got to them.”

“When you put together great shows, you’re a ringmaster. You need an angle, you’re selling tickets, you’re trying to get ratings, you want headlines and people talking about it,” Hearn explains.

“You need those characters because they’re priceless.”

With TV in mind, Hearn knew that while darts had a marketable raw product, it needed exposure. When Sky offered a deal, the ratings rocketed. TV brought quirks like fancy dress and signs, giving everyone their moment of fame. Hearn recalls a fan, famous for dressing as a chicken, calling him for a ticket.

“I said, ‘I’ve got a geezer on the phone saying he’s the chicken,’ and the team said, ‘oh, the chicken hasn’t got a ticket? We’ll get him in.’ He was the first I remember in full costume.”

The atmosphere became as much a part of the darts experience as the matches themselves. Fans weren’t just spectators, they were part of the show, whether through wild costumes, signs, or chants. Hearn understood that this sense of inclusion, where everyone had a role in the spectacle, was key to building a loyal following and an experience people wanted to come back to.

“You’ve got to spread love and happiness,” Hearn adds. “When people go to the darts, they have a great time and tell their mates the next day and this is the ultimate marketing tool.”

The potential Hearn saw has been fulfilled and more, with the 2024 World Champs Finals between Luke Humphries and Luke Littler attracting the highest ever non-football audience on Sky Sports at 4.8 million.

With Sky’s backing, Hearn’s ambitions took darts global. Packed arenas across Europe and even Madison Square Gardens in New York now sells out in minutes.

“Madison Square Gardens sold out for darts, with 70% of the crowd in fancy dress. Where did that come from?” Hearn says.

Hearn’s success isn’t waning, with demand driving tours in countries like Poland, Australia, and the Middle East.

“Whether it’s New York or Auckland, they can’t get enough. Broadcasters are coming in, paying more,” Hearn says.

With increasing revenue, Hearn views this as a chance to improve competitiveness and the sport’s quality.

“You’ve got to give kids a chance. If they can earn money, they’ll put in more hours, make sacrifices, and the snowball starts,” he says.

He’s delighted that players from humble, working-class backgrounds can benefit.

“I remember Nathan Aspinall, he got to the semi-finals, and he won £100,000. He said, ‘my house cost me 30 grand! It’s the most unbelievable day I’ve ever had.’”

With money and TV deals, Hearn believes darts will only improve for players. “Soon, they won’t just be millionaires, they’ll be multi-millionaires.”

Hearn’s commitment extends to the sport’s future through youth programs like the Junior Darts Corporation (JDC). Rising star Luke Littler, who joined the JDC at 10, is already making a significant impact, captivating audiences and redefining the sport for a new generation.

“He could be one of the greats, and that’s the sacrifice he has to make,” Hearn says. “He hit a nine-darter in his first match after the World Championship. We’re being entertained by greatness.”

Littler’s presence on the darts scene has been pivotal in attracting a younger audience to the sport. Littler connects with fans who might not have seen themselves in darts before. This younger fan base is invaluable, bringing fresh energy and ensuring the sport’s longevity in the newest chapter of the sports rapid rise.

As darts continues to evolve, Hearn’s influence is evident in every aspect of the sport. His relentless drive to elevate darts has created a thriving community which we as fans are the beneficiaries of.

Reflecting on his journey, Hearn is proud of his legacy. “In my own way, I’m building something for when I’m gone. I’d like darts players in 50 years to raise a glass to me. Is that big-headed? I don’t care. I know I’m doing a good job.”

To any doubters, his message is clear: “All those snobs, looking down their noses—fat blokes, pot bellies, smoking, drinking, darts? Look at them now. They’re the ones phoning me up, begging for a ticket. And I love it.”